By Shakiyla Huggins Oct 31, 2023

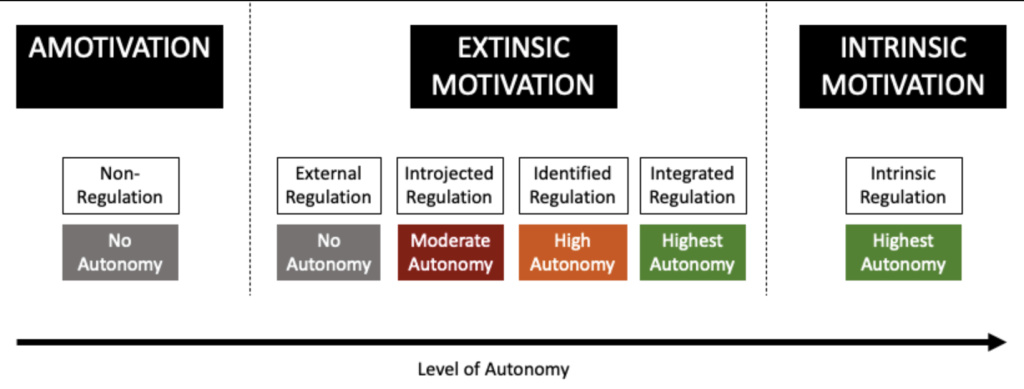

Motivation is a complex force that drives our behaviors, and to truly understand it, we must explore the continuum of self-determination. In a previous blog post, we discussed the Self-Determination Thoery and its insights into the core psychological needs that fuel our motivation to complete a task. We discovered that the three psychological needs of the Self-Determination Theory, autonomy, competence, and relatedness, are three very powerful needs that influence our goal-directed behaviors. More importantly, we discovered that these three needs were not chosen at random but emerged from multiple empirical processes and were the only way to psychologically justify the interpretation and integration of research results found while studying both internal and external motivations2.

Intrinsic Motivation: The Inner Flame

Intrinsically motivated people “feel that learning is important with respect to their self-images, and they seek out learning activities for the sheer joy of learning”

(Middleton & Spanias, 1999, p. 66).

Intrinsic motivation is the purest form of motivation, arising from the intrinsic value and interest one finds in an activity. It’s the drive that propels individuals to engage in tasks solely for the joy and satisfaction derived from the task itself. Unlike other forms of motivation, intrinsic motivation is not contingent on external rewards or reinforcements. Intrinsically motivated people “feel that learning is important with respect to their self-images, and they seek out learning activities for the sheer joy of learning” (Middleton & Spanias, 1999, p. 66).

There are two strands to the definition of intrinsic motivation1:

- emphasis on the idea that intrinsically motivated behaviors do not depend on reinforcements

- emphasis on the idea that intrinsically motivated behaviors are a function of basic psychological needs..

To be fully intrinsically motivated, there should be an absence of external reinforcements that try to help push participants to the desired goal, especially when these reinforcements take away from a person’s basic needs to be autonomous, competent, and relatable.

Extrinsic Motivation: The Influence of External Factors

Extrinsically motivated people desire recognition and try to avoid rejection. They aim for “favorable judgments of their competence from teachers, parents, and peers or avoiding negative judgments of their competence”

(Middleton & Spanias, 1999, p. 66).

Extrinsic motivation stands in contrast to intrinsic motivation, driven by external factors and rewards. It’s when individuals perform tasks with the expectation of receiving external incentives, recognition, or rewards. Extrinsically motivated people desire recognition and try to avoid rejection. They aim for “favorable judgments of their competence from teachers, parents, and peers or avoiding negative judgments of their competence” (Middleton & Spanias, 1999, p. 66).

However, when external forces like rewards or punishment drive motivation, it becomes controlled motivation. Each person involved in a task or activity becomes controlled by the desire to receive a reward or avoid punishment, which ultametly diminishes motivation once it is removed2 . Thankfully, extrinsic motivation can be internalized to become varying levels of autonomous. The self-determination theory accounts for these varying changes in extrinsic motivation through the concept of internalization. Simply put, people are naturally inclined to take external regulators and change them into internal ones to feel more self-determined while enacting them.

There are four types of extrinsic motivation classified along a continuum of increasing self-determination: external regulation, introjection regulation, identification regulation, and integration regulation5.

External regulation

At the lower end of this continuum is external regulation, where behaviors are directed by external rewards or constraints. This can sometimes undermine intrinsic motivation. Once the external regulator no longer controls a person, the motivation is not transferred outside of that particular task and is no longer maintained.

Introjection regulation

Moving up, we encounter introjected regulation, where external motivators are internalized, often through emotions like guilt or anxiety. The behavior is still fully dependent on the reward gained or lost based on the outcome of the results. However, now the individual attaches their internal regulator, such as self–esteem, to the outcome of the results, feeling more confident if the regulator is achieved and insecure if it is not.

Identification regulation

Identified regulation involves aligning external motivators with one’s personal values, rendering motivation more self-determined. This type of motivation is still extrinsic because the behavior is performed due to external regulators. However, the individual now identifies with the external regulator’s value, creating internally regulated behavior that is less controlling and more self-determined and autonomous1.

Integration regulation.

The pinnacle of extrinsic motivation is integrated regulation, where behaviors become fully integrated into one’s self-identity, resulting in self-determined extrinsic motivation. This form of extrinsic motivation is the most fully self-determined form of the four types of extrinsic motivation. The individual’s behavior is now integrated into other aspects of their self-identity, although it did not begin that way

Amotivation: The Abyss of Apathy

Amotivation is the state of having no motivation or intention to engage in a particular behavior4. It often arises when individuals perceive a disconnect between their actions and the desired outcomes. This state of apathy can be multifaceted and is closely tied to the frustration of basic psychological needs, including autonomy, competence, and relatedness1.

Amotivation isn’t a singular concept; it encompasses various dimensions, such as deficits in ability beliefs, effort beliefs, academic values, and task appeal4. Low ability represents the lack of sufficient ability or aptitude; low effort represents the lack of desire to invest the necessary energy; low academic value represents the lack of perceived importance or usefulness; and unappealing tasks represent the perception that the task at hand is a personally unappealing thing to do. When any of these dimensions are lacking, individuals may find themselves in the abyss of apathy, where they lack the drive to invest effort in a particular task.

Conclusion

In conclusion, our exploration of the continuum of self-determination reveals that motivation is not a one-size-fits-all phenomenon. It’s a multifaceted journey, where intrinsic, extrinsic, and amotivation coexist. Recognizing these different dimensions and the role of psychological needs in shaping our motivation can empower us to better understand our actions and, ultimately, lead more fulfilling lives.

References

- Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2000). The “What” and “Why” of Goal Pursuits: Human Needs and the Self-Determination of Behavior. Psychological Inquiry, 11, 227-268. Chinese Science Bulletin, 50(22), 227–268.

- Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2012). Motivation, Personality, and Development Within Embedded Social Contexts: An Overview of Self-Determination Theory. The Oxford Handbook of Human Motivation. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780195399820.013.0006

- Middleton, J. A., & Spanias, P. A. (1999). Motivation for Achievement in Mathematics: Findings, Generalizations, and Criticisms of the Research. In Source: Journal for Research in Mathematics Education (Vol. 30, Issue 1). https://www.jstor.org/stable/749630?seq=1&cid=pdf-reference#references_tab_contents

- Green-Demers, I., Legault, L., Pelletier, D., & Pelletier, L. G. (2008). Factorial invariance of the Academic Amotivation Inventory (AAI) across gender and grade in a sample of Canadian high school students. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 68(5), 862-880.

- Pelletier, L. G., Tuson, K. M., & Haddad, N. K. (1997). Client motivation for therapy scale: A measure of intrinsic motivation, extrinsic motivation, and amotivation for therapy. Journal of personality assessment, 68(2), 414-435.

- Van Roy, R., & Zaman, B. (2017). Why gamification fails in education and how to make it successful: Introducing nine gamification heuristics based on self-determination theory. In Serious Games and Edutainment Applications: Volume II (pp. 485–509). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-51645-5_22

Leave a comment